Anyone who follows my personal Instagram will know that one of my favourite places to eat in Tokyo is at OUT in Aoyama, where I can be found sipping one of the best Bloody Mary’s in town and having quiet truffle-induced foodgasms in the corner seat.

Out’s concept appealed to me as soon as it mentioned Led Zepplin, but the simplicity of the concept (one pasta dish, one glass of one, Led Zepplin on the record player) and design (yes, the pink sign) also drew me in. With it’s concrete interior and location on the quieter end of Aoyama, it’s nice place to hang out.

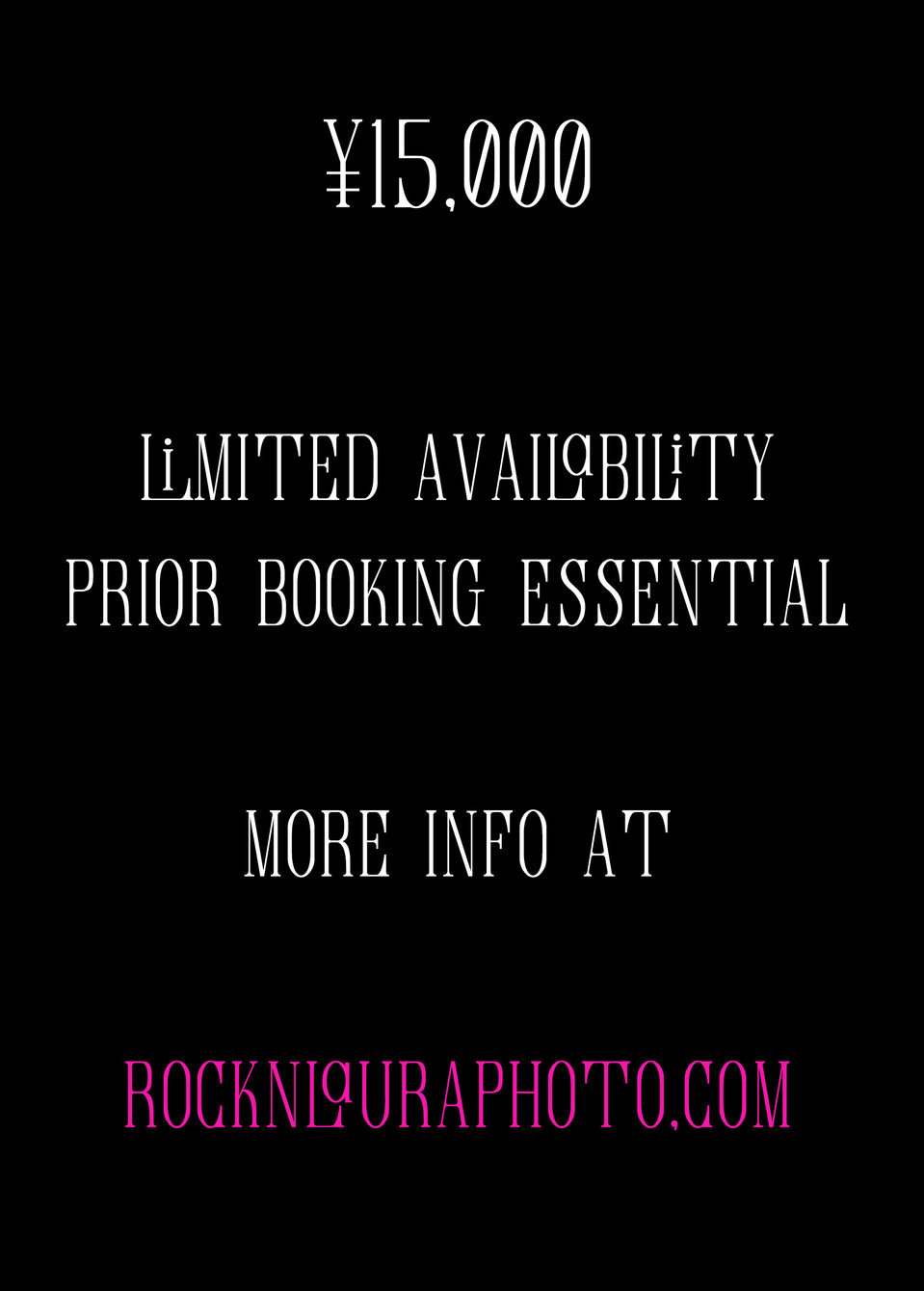

I’ve been thinking about organizing a photography event to promote what I call my “The Indie” package of headshots, and I think OUT is the best place to kick off this idea.

Click on the images below to see what my first event is about:

Places are limited so if you are interested in joining, please get in touch me with via my About page. The event promises to be a great opportunity to update your headshots and enjoy some delicious food, but also meet and talk with a group of fabulous Tokyo folks.

Oh! And here are few select food porn images from Instagram…

Rock-x-OUT

OUT-restaurant

headshots

toyko

portrait-photographer

truffles

brunch

On certain nights in November you may find yourself being drawn along in a crowd to Hanazono Jinja in Shinjuku’s San-chome district. The crowds thin as you edge towards the tourist hotspot of Golden Gai and begin to pass a line of yatai’s stretching down the street, nearby shop doorways full of people munching on grilled meat, plastic trays piled high with yaki-soba and the sad salt-crusted bodies of contorted fish skewered and grilled on chopsticks. Pressed in on every side by jostling bodies, wafts of meaty smoke tarring your nostrils and the distant chants of the approaching festival erupting above the general clamour, the Tori No Ichi festival experience is one that assaults all of the senses.

Navigating the crush of bodies to the main square of the shrine, a thick queue of people waits to pray to the otori-sama (the god of good fortune). Off to one side a pile of bamboo sticks, discarded daruma and various other gaudy items accumulate on a blue tarp. These are the previous year’s kumade - lucky charms for business and good fortune. One has been led to believe the shrine burns the kumade, their smoke scattering up to the heavens to meet the good will of the otori-sama.

Kumade come in all shapes and sizes – from 6-inch mini rakes to monstrous creations a good 1-metre across. The actual kumade itself is a rake (as in “raking in that cash”) and is adorned with other items said to bring good fortune. (When I tried to press people at the festivals I’ve attended as to what specific items represent all I was met with was “engi-mono” (good luck item). Everything was “engi”. Everything.)

My personal favourites are the kumade that explode out of bamboo sake boxes fashioned into lucky boats. Above them sit miniature gold and white sake barrels, and above those you may find all manner of adornment – maneki neko (for bringing in the cash), old-fashioned gold coins made from foiled card, red envelopes for receiving money, sails, dragons, bells, 5-yen coins, daruma, disco mirror-ball cats, plum blossom, cherry blossom, cranes, Shinto deities, Hello Kitty, miniature omikoshi (portable shrines), bamboo leaves, red snapper (おめでたい!) and sprigs of freshly harvested rice. To top it all off, your name is written on a plaque and added to your chosen lucky charm before the staff bestow luck upon you and your kumade by clapping and chanting over you (this is called tejime) before indulging in a sake tipple to finish.

During the Tori No Ichi festival Hanazono Shrine’s open grounds transform into a bewilderingly garish labyrinth of stalls at which to purchase good fortune with at least 50 different vendors hawking their wares to the crowd. The guys working the stalls at this festival are a tad more grizzled, and in some cases missing a few more digits than the average guy you get squished up against on a rush hour train. A Japanese friend suggested to me that perhaps the men missing fingers had lost them in gardening accidents, but there were more than a few green-fingered klutzes hanging around than seems credible; and if you take into account the location and the clientele, well, I’m going with my original observations.

Checking the names on the bamboo sticks adorning individual kumade, the businesses buying range from host and hostess joints, to rock bars, to live houses, and probably a lot more besides – after all, this is Shinjuku, an area which up until a few years ago was a unapologetic den of tolerated vice and all the other trappings of an “entertainment district”. Young men in slick suits sporting hairspray-stiff host hair meander about the festival with young women in towering heels, both of whom clearly yet to start work. Groups of older guys hiding behind sunglasses and wearing shiny shoes barge through the crowds with their lackeys parting the throng ahead of them as they disappear into blacked-out SUVs followed by kumade in the six-figure price range. Elsewhere folks sit sipping beers and laughing with each other in makeshift eateries. It’s all wonderfully loud and sleazy.

However, the Tori No Ichi festival that takes places in Asakusa on the east side of Tokyo seems a slightly different beast to Shinjuku; for starters, there don’t happen to be any carnivalesque performance troupes putting on freak-shows in a dubiously makeshift theatre. The streets leading up to Asakusa’s Juzaisan Chokoku-ji are cordoned off to traffic; the yatai stalls serve up Chinese-style pancakes, kebabs and French fries alongside the takoyaki and fish on a stick. A massive queue of people plunges straight through the grounds of the shrine and out on to the street, where shrine staff hover above the crowds on raised plinths waving white fronds over the assembled masses, blessing and purifying them as they wait to pray, all the while serenaded by a Gagaku (Imperial Court Music) orchestra playing inside the shrine buildings.

Asakusa is the original home of the Tori No Ichi festival. Dating back to the Edo era, it is said that the event began as a kind of harvest festival in the district of Hanamata (modern-day Adachi-ku). The festival takes place on the days of the Rooster (Tori) throughout November, with the first day being considered particularly auspicious.

Back in this more feudal era, peasants would give thanks by offering up roosters to their local deity – Hanamata - before heading down to Senso-ji in Asakusa to release the blessed fowl in front of the temple. What exactly happened next one can only imagine (happy chickens running around freely for the rest of their days?), but with humans being present, it perhaps involved the exchanging of monetary wagers and a chicken dinner later on. Once the authorities got wind of the gambling going on, the festival was moved down the road to Chokoku-ji, conveniently located next to a pleasure district, where it continues today. Wrapped up in this practice was the selling of lucky charms, the vendors themselves bringing in the cash to pay off their own feudal debts.

After my first experience at the festival, I was hooked. I was intrigued by the people, the sounds, the thousands of kumade hanging around and above me. I return almost every year, but I do confess that I don’t bring my lucky charms to be burned. One I passed on to my family and the other I re-appropriated for my kumade shoot.

The first inking of this project started around November 2017 and I wasn’t sure where the inspiration for this shoot came from until I returned a year later and found one of the vendors with oban-koban (old gold coins) and red envelopes stuck through her hair. This, coupled with my past obsession with crowns and halos, must have melded itself into the image I developed over the next year while I waited to get my hands on a new kumade. In the meantime, I also managed to locate an online store selling the basic materials to make these lucky charms and stocked up on a few items.

Once all the materials were gathered, assembling each kumade crown only took a few hours and involved a lot of hot glue, gold spray paint, polystyrene balls and a good soundtrack. Once made, they sat on my desk for about a month while I worked with SALZ Tokyo on the kimonos for the shoot and tracked down a model and make-up artist. Our first look consisted of an antique purple and gold kimono across which flows a gold and white phoenix, paired with an equally unusual obi decorated with paper cranes. Our second look involved an old kimono repurposed into a hakama-style skirt emblazoned with an orange chrysanthemum.

It being plum blossom season, I wanted to get something with a good background of blossoms in the background and after a lot of scouting and deliberation I settled on Yushima Tenjin in Bunkyo-ku for our first location. Plum blossom season meant that we would be dealing with the weekend Tokyo crowds, so we shot early at about 9.30am. It was already packed but luckily the back steps up to the temple are relatively off-piste which gave us much more room to work with. The second location I had hoped for was Hanazono Jinja, which seemed fitting, as it was the place I got my original inspiration, but we were turfed off immediately (yes, I was trying to be sneaky and disrespectful). My tendency to fret about things at 3am paid off though, and unfazed, we relocated a few streets over to the back streets of the Golden Gai area. Ultimately, I think this resulted in a much better look than I had planned, with the first shoot looking more traditional while the second became more urban and edgy.

All in all, this project took about 2 years to put together and cost more a fair bit. It’s the first time I’ve headed my own shoot bigger shoot and while it took a while it get going, I enjoyed the process and learned a great deal from it.

Text and Photos: Laura Cooper